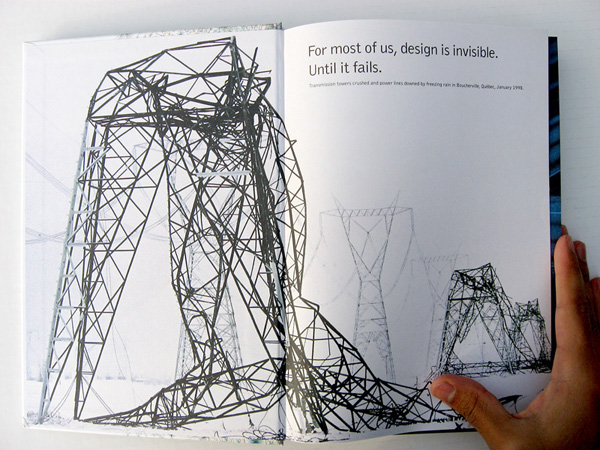

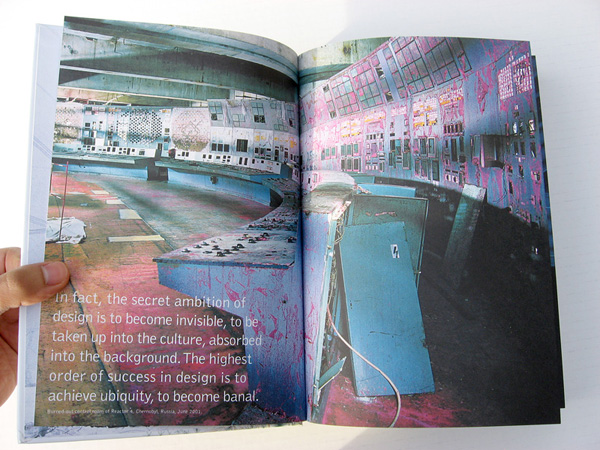

I was inspired by Silas’ Seeing 20/20 posting to write this entry, as it briefly addressed some of the issues i’ve been thinking about in relation to graphic design. In recent years, our profession has been transformed by the influence of other disciplines. Four years ago, during the inaugural class of the Institute without Boundaries, our class spent one year studying the question “What is the future of design?” The Massive Change book, one of the results of this post-graduate design program, opened up by stating that “design is invisible until it fails,” referring to the infrastructures that sustain modern life as objects of design (i.e. transportation systems, the internet, cities, etc.) By opening up design conversations beyond 20th century models of production, broader understandings of the profession that embrace design within larger systems emerged as a result of this project. As Silas mentioned, the graphic design profession was coined nearly a century ago. For the most part of last century, the graphic design profession remained fairly stable until the last couple of decades.

First spread of Massive Change book. Photograph shows transmission towers crushed and power lines downed by freezing rain in Boucherville, Quebec, January 1998.

Second spread of Massive Change book. Photograph shows burned-out control room of Reactor 4. Chernobyl, Russia, 2001.

Although the notion of a “designer-less design office” makes no sense at first sight, it raises a lot of issues that graphic designers are struggling with today. Rapid technology changes have swept the industry and drive some of the major innovations in the field today. Design businesses are constantly required to add value to their products and services in face of global competition. Many of us are left wondering what just happened to our tidy understanding of graphic design. I believe that a more engaged design practice could be a way forward for graphic design to continue being relevant.

My design studio, Work Worth Doing, might be a designer-less office. However, I do not seek autonomy as Silas’ concept suggests. Instead, our office seeks a more direct engagement with the world. Even though I am the only “design-trained” designer at the office, we operate as a design studio. Our focus is on systems designs often born out of our own initiative that are parsed through inter-disciplinary inquiry. The resulting outcomes address social or environmental challenges. For example, our Now House project involves the design of a home retrofit system for a wartime house that reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 6 tons on an annual basis and could potentially be applied to millions of existing wartime houses in North America. It is through a direct engagement with architects, engineers, and energy specialists that this project emerged. Other projects have required us to engage with political scientists, economists, and sociologists. My roles have been paradoxically those of a graphic designer and generalist designer.

As designers, we often forget to look at the past for answers to our profession’s current ontological struggles. Buckminster Fuller, designer, architect, and inventor, strived to find an answer to the relevance of design in the world, or how design can “address humanity’s present and future needs.” The legacy of his work is now articulated by the Buckminster Fuller Institute as design science, a design practice that is comprehensive, systematic, anticipatory, ecologically responsible, able to withstand empirical testing, and replicable.

In face of current scientific knowledge that indicates humanity’s current lifestyle can not be sustained for the remainder of this century, I find Fuller’s design legacy very relevant. Recent studies suggest that climate change, the result of human activity is of great concern, warning that if the earth’s temperature were to raise by two degrees celsius, irreparable damage to the world’s biosphere, societies, and economy would be caused. However, recent studies by WWF and UNEP suggest it is still possible to prevent such damage if we act today simply by scaling what we already know how to do. In other words, existing technologies and knowledge would suffice to solve the world’s climate change problem.

Embracing complexity with the world at large remains a challenge for our profession, but some designers –not only graphic designers — are beginning to address this issue. The evolution of our profession is a complex process, but I believe that a commitment to engage beyond traditional notions of graphic design and addressing broad challenges is a positive step forward for our field.